During his Senate confirmation hearings, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suggested he wouldn’t undermine vaccines.

He also said he wouldn’t halt congressionally mandated funding for vaccination programs, nor impose conditions that would force local, state or global entities to limit access to vaccines or vaccine promotion.

“I’m not going to substitute my judgment for science,” he said.

Yet the Department of Health and Human Services under Kennedy took unprecedented steps to change how vaccines are evaluated, approved and recommended — sometimes in ways that run counter to established scientific consensus.

Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. testifies Tuesday during a House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing in Washington.

Childhood vaccine schedule

Sen. Bill Cassidy, a physician who was unsettled about Kennedy’s antivaccine work, said Kennedy pledged to him that  existing vaccine recommendations.

People are also reading…

"I recommend that children follow the (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) schedule. And I will support the CDC schedule when I get in there,” Kennedy said at his Senate confirmation hearing.

Kennedy also said he thought the polio vaccine was safe and effective and that he wouldn’t seek to reduce its availability.

However, °±đ˛Ô˛Ô±đ»ĺ˛âĚý the childhood vaccine schedule that prevents measles, polio and other dangerous diseases. And the National Institutes of Health in early March  about ways to improve vaccine trust and access.

±á±đĚý April 9 that “people should get the measles vaccine, but the government should not be mandating those,” then continued to raise safety concerns about vaccines.

On May 22, °±đ˛Ô˛Ô±đ»ĺ˛âĚý that, among other things, questioned the necessity of mandates that require children to get vaccinated for school admission and suggested that vaccines should undergo more clinical trials, including with placebos. The report has to be reissued later because the initial version cited .

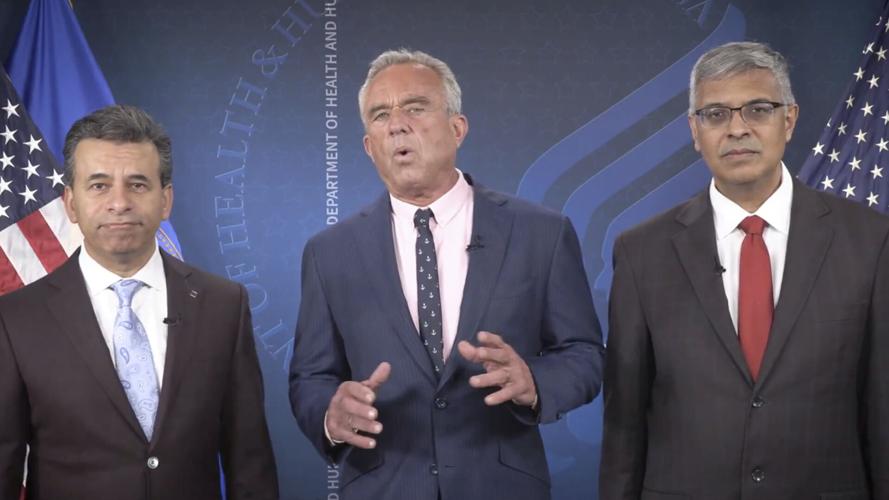

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. speaks alongside Food and Drug Administration Administrator Dr. Martin Makary, left, and Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, director of the National Institutes of Health, as they announce that the government would no longer endorse the COVID-19 vaccine for healthy children or pregnant women.

CDC vaccine recommendations

At the confirmation hearing, Cassidy asked Kennedy: "Do you commit that you will revise any CDC recommendations only based on peer review, consensus based, widely accepted science?"

Kennedy replied, “Absolutely,” adding he would rely on evidence-based science.

Yet on Feb. 20, HHSÂ Â of outside vaccine advisers.

The CDC’s vaccine advisory panel met April 16 and  that people 50 to 59 with certain risk factors should be able to get vaccinated against respiratory syncytial virus, and endorses a new shot that protects against meningococcal bacteria. As of late June, the CDC and HHS haven’t acted on the recommendations.

°±đ˛Ô˛Ô±đ»ĺ˛âĚý May 27 that COVID-19 vaccines are no longer recommended for healthy children and pregnant women — a move immediately questioned by several public health experts. No one from the CDC, the agency that makes such recommendations,  in the video announcing the changes.

U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced that the United States is withdrawing its support from the global vaccine alliance Gavi.

On June 9, °±đ˛Ô˛Ô±đ»ĺ˛âĚý all 17 members of the science panel that advises the CDC on how vaccines should be used.ĚýTwo days later, °±đ˛Ô˛Ô±đ»ĺ˛âĚý new vaccine policy advisers to replace the panel he dismissed. They include a scientist who rose to prominence by relaying conspiracy theories around the COVID-19 pandemic and the vaccines that followed, a leading critic of pandemic-era lockdowns, a business school professor and a nurse affiliated with a group that is widely considered to be a leading source of vaccine misinformation.

The panel  Wednesday that it will establish a work group to evaluate the “cumulative effect” of the children’s vaccine schedule. The same day, Kennedy announced the U.S.Ěý the vaccines alliance Gavi. He accused the group, along with the World Health Organization, of silencing “dissenting views” and “legitimate questions” about vaccine safety.

Kennedy's vaccine advisers  Thursday that people receive flu shots free of an ingredient that antivaccine groups have falsely tied to autism. The vote came after a presentation from an anti-vaccine group’s former leader. A CDC staff analysis of past research on the topic is removed from the agency's website because, according to a committee member, the report wasn't authorized by Kennedy’s office.

The Trump administration’s vaccine advisers on Thursday endorsed this fall’s flu vaccinations for just about every American but with a twist: Only use certain shots free of an ingredient antivaccine groups have falsely tied to autism.

Vaccine approvals and review standards

At the Senate hearing, Cassidy asked Kennedy if he would keep FDA's historically rigorous vaccine review standards.

“Yes,” Kennedy replied.

Kennedy forced the FDA’s top vaccine official  March 29. The official, Peter Marks, said he feared Kennedy’s team might  from a vaccine safety database.

On May 6, Kennedy named , an outspoken critic of the FDA’s handling of COVID-19 boosters, as the FDA’s vaccine chief.

After a delay, the FDA  for its COVID-19 vaccine May 16 but with unusual restrictions: The agency says it’s for use only in adults 65 and older or those 12 to 64 who have at least one health problem that puts them at increased risk from COVID-19.

Top officials  for seasonal COVID-19 shots to seniors and others at high risk May 20, pending more data on everyone else. The FDA urged companies to conduct large, lengthy studies before tweaked vaccines can be approved for healthier people, a stark break from the previous federal policy recommending an annual COVID-19 shot for all Americans 6 months and older.

FDA on May 30  made by Moderna but with the same limits on who can get it as Novavax's shot.

The Gates Foundation is Gavi’s largest private donor, having contributed $7.7 billion over the past 25 years. (Scripps News)

Bird flu vaccine

At his confirmation hearing, Kennedy said he would support the development of a vaccine for H5N1 bird flu.

The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, an HHS agency, on May 28  in awards to Moderna to develop a vaccine against potential pandemic influenza viruses, including the H5N1 bird flu.

What happens to health research when 'women' is a banned word?

What happens to health research when 'women' is a banned word?

Daniella Fodera got an unusually early morning call from her research adviser this month: The doctoral student's fellowship at Columbia University had been suddenly terminated.Ěý

Fodera sobbed on phone calls with her parents. Between the fellowship application and scientific review process, she had spent a year of her life securing the funding, which helped pay for her study of the biomechanics of uterine fibroids—tissue growths that can cause severe pain, bleeding and even infertility. Uterine fibroids, an underresearched condition, impact as they age.

"I'm afraid of what it means for women's health," Fodera said. "I'm just one puzzle piece in the larger scheme of what is happening. So me alone, canceling my funding will have a small impact—but canceling the funding of many will have a much larger impact. It will stall research that has been stalled for decades already. For me, that's sad and an injustice."

Fodera's work was a casualty of new federal funding cuts , one of several schools targeted by the Trump administration. The administration is also , while trying to .Ěý

Researchers say threats to federal research funding and President Donald Trump's promise to eliminate any policy promoting "" are threatening a decades-long effort to improve how the nation studies the health of women and queer people, or improve treatments for the medical conditions that affect them, reports. Agency employees not to approve grants that include words such as "women," "trans" or "diversity."Â

That could mean halting efforts to improve the nation's understanding of conditions that predominantly affect women, including endometriosis, menopause, infectious diseases contracted in pregnancy and pregnancy-related death. It could also stall research meant to treat conditions such as asthma, heart disease, depression and substance abuse disorders, which have different health implications for women versus men, and also have outsized impacts on LGBTQ+ people and people of color—often underresearched patients.

"I want every generation to be healthier than the last, and I'm worried we may have some real setbacks," said Dr. Sonja Rasmussen, a professor and clinician at Johns Hopkins University who studies the consequences of pregnancy-related infections and the causes of birth defects.

The United States already lagged in promoting scientific inquiry that considered how sex and gender can influence health—and has a recent history of focusing research on White men. Less than 50 years ago, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from including women who could become pregnant in clinical trials for new medical products, leaving it often unclear if U.S.-based therapeutics were safe for them. It wasn't until 1993 that clinical trials to include women and "individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds."

Around that same time, the federal government launched offices within , and that focused on women's health and research. Since then, efforts to consider gender in medical research have progressed, if unevenly. A last fall from the National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine found that in the past decade, the level of federal funding devoted to women's health had actually declined relative to the rest of the NIH's budget.Ěý

The report, requested by Congress, also found that researchers still struggled to understand the implications of common conditions such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids, the long-term implications of pregnancy, or gender gaps in mental health conditions—all areas where Black women in particular experience worse health outcomes or face heightened barriers to appropriate treatment. Investments had stalled in looking at how sex and gender interact with race or class in influencing people's health outcomes.Ěý

The report ultimately called for an additional $15.8 billion over the next five years to address the gaps. Now, efforts to cut federal research funding and limit its acknowledgment of gender could thwart forward momentum.

"If we are banning this study of these issues, or deciding we're not going to invest in that work, it freezes progress," said Alina Salganicoff, a lead author on the report and vice president for women's health at KFF, a nonpartisan health policy research organization.

Already, researchers whose work touches on sex or gender are anticipating losses in federal funding, which they fear could imperil their work moving forward. Some have already had their grants terminated. Many specified that they were not speaking as representatives of their employers.Ěý

Whitney Wharton, a cognitive neuroscientist at Emory University, learned on Feb. 28 that she would no longer receive federal funding for her multiyear study looking at effective caregiving models for LGBTQ+ seniors at risk of developing Alzheimer's. that queer adults may be at greater risk of age-related cognitive decline, but they are far less likely to be the subject of research.ĚýÂ

Wharton is one of numerous scientists across the country whose work was terminated because it included trans people, per letters those researchers received from the NIH. "Research programs based on gender identity are often unscientific, have little identifiable return on investment, and do nothing to enhance the health of many Americans," the letter said.Ěý

Though Wharton's work focused on queer adults, it proposed caregiving models that could apply to other people often without family support structures who are at heightened risk for Alzheimer's as they age.

"The sexual and gender minority community is more likely to age alone in place. We're less likely to be married or have children," Wharton said. "These additional roadblocks are not only unnecessary but they are unnecessarily cruel to a community that's already facing a lot of hardship."

One of Wharton's collaborators on the study is Jace Flatt, an associate professor of health and behavioral sciences at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who also received separate notice from the NIH that their research beyond the study had been terminated. Flatt studies LGBTQ+ people and their risk for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, as well as thinking about their needs for care.

Flatt said NIH funding for three of their studies have been canceled in recent weeks, as well as a Department of Defense-funded grant looking at veterans' health that included LGBTQ+ people. The defense letter stated the research did not align with Trump's that recognizes only two sexes, male and female.

Flatt estimates about $4.5 million in federal funding was cut from their research, requiring some staff layoffs.Ěý

"I made a personal commitment to do this work. Now I'm being told, 'Your research doesn't benefit all Americans, and it's unscientific,' and basically that I'm promoting inaccurate research and findings. The tone comes across as like it's harmful to society," they said. "I'm a public health practitioner. I'm about improving the health and quality of life of all people."Â

Jill Becker, a neuroscientist at the University of Michigan, uses rodent studies to better understand how sex differences can affect people's responses to drug addiction and treatment. Her work has helped suggest that some forms of support and treatment can be more effective for male rats and others for female ones—a divide she hopes to interrogate to help develop appropriate treatments for people who are in recovery for substance use disorder, and, in particular, better treatment for cisgender men.Ěý Â

Becker's studies were singled out in a Senate , a Republican, who characterized it as the type of wasteful research that shouldn't continue. Because she looks at sex differences, she anticipates that when her NIH funding finishes at the end of the year, the agency will no longer support her—a development that could eventually force her lab and others doing similar work to shut down entirely.

"If we no longer include women or females in our research, we're obviously going to go back to not having answers that are going to be applicable to both sexes," she said. "And I think that's a big step backward."

Government shuts down research it doesn't understand

The NIH did not immediately respond to a request for comment.Ěý

In interviews with The 19th, academics broadly described a sense of widespread uncertainty. Beyond federal funding, many are unsure if they will still be able to use the government-operated databases they have relied on to conduct comprehensive research. Others said the NIH representatives they typically work with have left the organization. Virtually all said their younger colleagues are reconsidering whether to continue health research, or whether a different career path could offer more stability.Ěý

But the Trump administration has remained steadfast. In his recent joint address to Congress, Trump praised efforts to cut "appalling waste," singling out "$8 million to make mice transgender"—a framing that misrepresented studies involving asthma and breast cancer.Ěý

The government's rhetoric is now deterring some scholars from certain areas of study, even when they recognize a public health benefit. One North Carolina-based psychologist who studies perinatal mental health and hormone therapy for menopausal people said her team had considered expanding their research to look at that treatment's mental health implications for trans people.Ěý

"It's important, and I don't have any way of doing that work at the moment," said the psychologist, who asked that her name be withheld from publication because she fears publicly criticizing the NIH could jeopardize research funding. "There is potential for that line of research in the future, but not in this funding environment."

The concerns spread beyond those who receive government funding. Katy Kozhimannil, a public health professor at the University of Minnesota, doesn't receive NIH support for her research on pregnancy-related health and access to obstetrics care in rural areas. Her work has looked at perinatal health care for Native Americans, including examining intimate partner violence as a risk factor for pregnancy-related death. The findings, she hopes, could be used to help develop policy addressing the fact that Native American and Alaska Native people are more likely to die during pregnancy than White people.Ěý

But future studies may not be possible, she fears, because of an interruption in data collection to PRAMS, a comprehensive federal database with detailed information about Americans' pregnancy-related health outcomes. Within the first weeks of the new administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) told state health departments to stop collecting data to maintain the system, while saying that it will be brought back online once it is in compliance with the new government diversity policies.

Kozhimannil and other scholars in her field are worried about what that means—and whether PRAMS will continue to publish information showing outcomes by race or geography. Those would be tremendous omissions: A vast body of data shows that in the United States, Black and American Indian women are at elevated risk of dying because of pregnancy. People in rural areas face greater barriers to reproductive health care than those in urban ones. Without the information PRAMS is known for, Kozhimannil said, it will be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to conduct research that could address those divides.Ěý

It's not clear if or when that information will be available, she added. One of her doctoral students requested access to PRAMS data in January and has still not heard back on whether it will be made available to her—a delay that is "not normal," Kozhimannil said.

"It's hard to imagine getting toward a future where fewer moms die giving birth in this country, because the tools we had to imagine that are not available," she said. "I'm a creative person and I've been doing this a while, and I care a lot about it. But it's pushing the boundaries of my creativity and my innovation as a researcher when some of the basic tools are not there."

Paul Prince, a spokesperson for the CDC, acknowledged "some schedule adjustments" to PRAMS to comply with Trump's executive orders, but claimed it does not affect the program's continuation. He added: "PRAMS was not shut down."

"PRAMS remains operational and continues its mission—identifying issues impacting high-risk mothers and infants, tracking health trends, and measuring progress toward improving maternal and infant health," he said in an email.

Trump puts the brakes on funding of women's health research initiatives that had bipartisan support

It's unclear the scope of long-term ramifications to health research, but Kathryn "Katie" Schubert is tracking it closely. She is the president and CEO of the Society for Women's Health Research, an organization that has advocated on decades of congressional policy. In 2005, the group released that found just 3 percent of grants awarded by NIH took sex differences into consideration.

In February, her organization and other groups sent a letter to the administration highlighting the need to continue prioritizing women's health research.

"We have gotten to the point where we know what the problems are. We know where we would like to try to solve for—so how are we going to find these solutions, and what's the action plan?" she told The 19th.

In the past, Trump has shown a willingness to address women's health inequity in at least in some arenas. A 2016 law, signed by former President Barack Obama, on how to better incorporate pregnant and lactating people into clinical trials. Trump continued that work under his first administration.

Still, when pharmaceutical companies against COVID-19 in 2020, they at first did not include pregnant or breastfeeding people in clinical trials, despite federal policy encouraging them to do so and data showing that pregnant people were at higher risk of complications from the virus. Those same vaccine trials also initially excluded people who were HIV positive—a policy with particular ramifications for trans people, who are living with HIV at a higher rate than cisgender people—and only after public outcry.

Trump returned to power on the heels of a renowned federal focus on women's health research and gender equity. In 2023, President Joe Biden announced the first-ever to address chronic underfunding.

During his final State of the Union address, Congress to invest $12 billion in new funding for women's health research. He followed that with directing federal agencies to expand and improve related research efforts.

In December, former First Lady Jill Biden led a conference at the White House where she highlighted nearly $1 billion in funding committed over the past year toward women's health research. She told a room that included researchers: "Today isn't the finish line; it's the starting point. We—all of us—we have built the momentum. Now it's up to us to make it unstoppable."

The Trump administration rescinded the council that oversaw the research initiative. The press office for the Trump administration did not immediately respond to a request for comment.Ěý

Schubert said prioritizing women's health has bipartisan support, and she remains hopeful of its popularity across both sides of the aisle. She also recognizes it could mean a new era of investment sources.

"We'll continue as an organization, of course, with our partners, to work to fulfill our mission and to advocate for that federal investment and to make sure that the workforce is there and make that policy change. We'll do that under the best of times and the worst of times," she said. "But I think when we think about sort of the broader community—we've seen other philanthropic organizations come in and say, 'OK, we're ready to partner and really make this investment on the private side.'"

Women's health research has more visibility than ever, and not just because some high-profile celebrities and media personalities are investing time and money toward addressing it. Social media algorithms are also increasingly targeting messaging around women's health and wellness. Economists estimate that in economic returns.

"Yes, we are in a very difficult time when it comes to the federal budget," Schubert said. "Even in spite of that, there will be opportunities to see this issue continue to rise to the top."

The speed and scope of those opportunities may not extend to researchers like Flatt in Nevada. They plan to appeal their NIH funding cuts, but they don't feel optimistic—in part because the letters state that no modifications of their projects will change the agency's decision.

Flatt noted that in recent weeks, some people have suggested that they exclude transgender people from their studies. Flatt said excluding people of all genders is not pro-science.

"I refuse to do that," they said. "The administration is saying that it needs to be for all Americans. They are Americans."

Fodera, the Columbia doctoral student, will continue her research on uterine fibroids for now, due partly to timing and luck: The fellowship had already paid out her stipend for the semester, and her adviser pooled some money together from another source.

But the future of her fellowship is in question, and such research opportunities . Fodera is expected to graduate in a few months, and plans to continue in academia with the goal of becoming a professor. She's looking for a postdoctoral position, and is now considering opportunities outside of the United States.

"This is really going to hurt science overall," she said. "There is going to be a brain drain from the U.S."

was produced by and reviewed and distributed by Stacker.

Retirement, interrupted: Why those over 55 are a fast-growing segment of the workforce

Retirement, interrupted: Why those over 55 are a fast-growing segment of the workforce

Joan Madden-Ceballos, a 65-year-old health care administrator, has a working life in California many would envy. Her work is flexible, fulfilling, and something she enjoys going back to day after day. "I'm a baby boomer, so work is sort of ingrained in our lives," .

While it may sound unusual for some to work past what many consider the "golden years" of retirement, Madden-Ceballos is among the increasing number of Americans who have stuck around the workforce longer as they age, according to federal data. Per 2023 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, are 55 or older. Three in 20 working Americans are aged 55 to 64, while roughly 7 in 100 are older than 64.

From 2003 to 2023, there was a sizable jump in people 55 and older still in the workforce—nearly a 74% increase—but there were also profound jumps in those working who are 65 and older. The number of workers aged 65 to 74 jumped 139%, and those 75 and older increased by 113%.

explored data from the to examine why the aging workforce in the United States is working past the typical retirement age.

With longer lives and better health, seniors are choosing to work

There are a few reasons why many seniors are choosing to work past their retirement age.

Older Americans today are living longer and maintaining their physical independence longer. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates, the average 65-year-old was , compared to just . A 2023 study of 5.4 million older Americans published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health also found that across 10 years, the number of people 65 and over with functional limitations .

Work may be a way to stay active in society for some older Americans. Workers aged 50 and older told researchers their jobs have , according to the 2024 University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging. Nearly half said that work gave them a sense of purpose and kept their brains sharp. This reality is even more consistent for workers aged 65 and older, with 9 in 10 saying that working helped their overall well-being.

The nature of jobs has also changed. Nicole Maestas, professor of economics and health care policy at the Harvard Medical School, noted that " in today's information economy, so for some, it is easier to continue working."

A survey of 2,000 individuals aged 50 to 79 published by the National Bureau of Economic Research also found that job characteristics . According to researchers, nearly a third would likely keep working past 70 if their job offered flexible hours compared to just a sixth without that option. Job stress, the physical and mental demands of the job, telecommuting options, or commuting times were other factors that played into that decision.

Still, a sense of purpose and job characteristics are only part of the picture. When asked why workers aged 50 and older might keep working, the top reasons the University of Michigan poll respondents gave were related to finances. Nearly 4 in 5 (78%) workers said financial stability is what keeps them clocking in, followed by saving for retirement and access to health insurance.

Some older Americans can't afford to stop working

On multiple surveys, people reported a bleak savings picture and perspective on retirement. For a 2024 AARP survey, reported not having enough savings to be "financially secure" in retirement. In 2023, 2 in 5 respondents told Gallup they expected "," down from 3 in 5 in 2002.

Numerous factors could be driving this sentiment.

People could be working longer because a dollar does not stretch as far as it used to. , while the cost of goods, measured by the Consumer Price Index, has steadily increased. Renting or buying a home than decades ago. Gen Z dollars could buy of what baby boomers could in their 20s, according to Consumer Affairs.

A few decades ago, pensions were also more common. Employers managed the money for their employees' pensions, known as defined benefits plans, and paid employees for life after retirement. It was a guaranteed income benefit that typically started at a specific age, like 62, incentivizing older workers to plan for retirement. Benefit pensions became less common because of the .

Why older Americans are working longer

By the 1980s, defined contribution plans like 401(k)s became more widespread. These plans typically lack age-specific requirements, found Courtney Coile, a researcher in the economics of aging and health at Wellesley College, . A quarter of those return to work within six years in part- or full-time jobs.

Researchers from the Georgetown Center for Retirement Initiatives also found that while current estimates use older generations with pensions as a basis for forecasts, newer retirees tended to draw down their savings at much faster rates, fueled in part because of longer life expectancies that increased the need for . Consequently, new retirees may exhaust their 401(k) assets by 85 years of age, likely outliving their savings.

Some older Americans may not even have enough to begin with. The Government Accountability Office found in 2024 that did not have any retirement savings as of 2022, and a third of households with a worker 55 or older did not have any retirement or defined benefit plan set by an employer to fall back on.

People may be working longer to delay pulling Social Security benefits, even increasing their monthly payments. Yet the existing financial safety net for older Americans is fraying. Social Security . The additional source of income for older workers, driven by a lifetime of workers' wages, is without congressional action, stated the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds in its 2024 annual report. Social Security and Medicare alone are insufficient for people to make ends meet. Half of older adults living alone, as well as 1 in 5 older couples, "," according to a 2022 study led by three gerontologists from the University of Massachusetts Boston.

"There's a myth that Social Security and Medicare miraculously take care of all of people's needs in older age," Ramsey Alwin, president and chief executive of the National Council on Aging, . "The reality is they don't, and far too many people are one crisis away from economic insecurity."

What can be done better?

need to happen to help older Americans—and the nation—prepare for the future as aging workers participate more in the economy.

Scholars from the AARP Public Policy Institute, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and the Brookings Institution are proponents of workers setting up dedicated emergency accounts that separate one's emergency savings from general savings, making it less likely to be spent for other needs. They also suggest that states explore putting employees into automatic individual retirement accounts unless they already have retirement plans. Vermont and 17 other states are already , according to Time. They are also encouraging the government to explore ways to make it easier for employees to move their retirement balances from one plan to another, making their hard-won savings less likely to be abandoned or forgotten.

Employers can also , knowing that older Americans will only be more present in the workplace. Employers can promote skills training for everyone, allow flexible work options, give workers a say in their schedules and work locations, and create an ergonomic workplace that addresses hazards more commonly faced by older workers, who may be more adversely affected by slips and trips. These changes may also benefit all generations in the workplace.

Strengthening financial security for an aging workforce

Leaders can also push back on harmful myths that affect older workers like their supposed opposition to change or decreased productivity. AARP research has found that aged 50 and older reported seeing or experiencing age discrimination in the workplace.

Finally, older employees who may not have enough money can try to improve their retirement outlook with a , CNBC reported. The first step is to calculate how much they might actually need for retirement rather than guessing. The , developed by the Gerontology Institute at the University of Massachusetts Boston, is a tool that can help older workers pinpoint how much they need.

Some workers may also consider shifting to part-time work before retiring fully.

Workers should also take advantage of IRS tax incentives aimed at helping workers save for the future. The could provide up to 50% of one's contribution based on a filer's adjusted gross income. There are also workers aged 50 and older can make to add to their retirement savings beyond the plan type or IRA contribution limit.

By 2040, people 65 and older are expected to comprise , according to the Administration for Community Living, an operating division of the Department of Health and Human Services. As the nation ages, the country will increasingly depend on older workers to fuel the country's economic activity. It would be ideal to have a working future, like Star Bradbury, the Gainesville, Florida-based author of "Successfully Navigating Your Parents' Senior Years."

"I know for myself that I am happier when I am working and happier when I am helping other people," Bradbury . She said that, at 75 years old, her job as an author and senior living strategist gave her "a sense of purpose and don't mind earning a little extra money. All those things add up to keep me working."

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by SofĂa JarrĂn. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

originally appeared on and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.